There is no map of the matagi people, a mountain-dwelling group of hunters found in the highlands of northern Honshu, the largest island of Japan. They exist in the borderlands of the world we know, in step with the wild beings of this planet, taking spiritual guidance from an ancient god of the old world. Their traditions are passed down by word of mouth from generation to generation, parents to children. There are very few written records of their practices, traditions and history. No one knows how many people still practice the way of the Matagi, but it is largely seen as a dying way of life.

A fascination with the melding of tradition and the march of modernity led documentary storytellers Javier Corso and Alex Rodal into the path of the Matagi. In 2017, they began a journalistic quest to understand this ancient culture.

History

Evidence of hunting clans of Matagi have been documented from the 16th century. They’re known to have supplemented crop farming with the hunting of black bears, boars, serows and anything else the mountains had to offer. The black bear is considered their most important prey, both for its dangerousness and divine representation.

At the foundation of the Matagi ethos and culture is an inherent belief in the conscious presence of nature as personified by the goddess of the mountain — Yama-no-Kami.

Scott Schnell, notable researcher on the Matagi, explains, “As a conscious presence, [Yama-no-Kami] is there to…place limits on abusing privilege — so you don’t take more than you need because that will anger the Yama-no-Kami, and she would withhold her favor from you. [This belief] acts as a kind of rudimentary conservation ethic: take only what you need.”

Schnell’s reflections suggest a sacred trust between the mountain goddess and the Matagi, highlighting the unique way in which the Matagi conduct themselves in the natural world.

Current Day

The number of Matagi has been declining for decades. This is largely attributed to the exodus of young people from rural communities combined with a rapidly aging Japanese population.

Hideo Suzuki, leader of the Matagi community of Animatagi (considered the origin of the Matagi culture), explained that many people have retired from a lifestyle that is mentally and physically demanding. In Animatagi, there are only 10-15 Matagi hunters left.

While the last gasps of the culture cling to relevance in a modern world, the Fukushima nuclear incident in 2011 hastened the degradation of the Matagi communities. As a result of the declared “dead zones” around the nuclear power plant, the state prohibited the sale of wild game meat due to radiation risk. Simultaneously, many Matagi communities voluntarily opted to cease annual hunts considering the contamination risk, thus ending a source of income that had been relied on for centuries.

The ban was lifted in 2017, five years after its implementation. According to Schnell, this fallow period was likely responsible for a significant drop in the number of people practicing the Matagi ways, as other income streams were procured and the burden of maintaining firearms licenses was not worth the increasing effort. After a long period without annual hunting rituals, many people chose not to return to their old traditions.

The majority of Matagi seem resigned to the idea that their generation will be the last to seek the spoor of the black bear across snow-covered mountains — the last Matagi bear hunters.

Complexities of Controversy

As is the case with cultural hunting practices the world over, the Matagi’s are under increasing scrutiny. This is compounded by the red listing of Asiatic black bears by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN). The Japanese black bear is a subspecies classified as “vulnerable” according to the IUCN (not endangered).

Interestingly, Japan is one of the few countries where populations of this species are stable or growing. In a twist of irony, this is likely due to the efforts of the Matagi, who together with local governments carry out the task of population control and protection against illegal poachers.

The First Matagi Woman

There is, however, a glimmer of a new future for the Matagi hunters. In 2019, Corso and Rodal were introduced to Hiroko Ebihara, the first woman granted permission to hunt with the Matagi. Over the last eight years, she has studied and practiced to become the first Matagi woman.

She describes her path to the mountains and the Matagi in this way:

“I made Japanese-style paintings, mainly of animals. So I spent many hours at the zoo drawing. However, I felt that I was missing something, because in the zoo I was not able to capture the real essence of animals.

“I needed to know how they lived and behaved in their natural habitat — to experience real nature.”

Hiroko began to think more deeply about her connection to the natural world and her place in the landscape. To feed this curiosity, a mentor suggested she witness a bear hunt with the Matagi as part of her journey of discovery.

“At first, I had no intention of being a Matagi at all,” she says. “My purpose was to see the bears in their pure and natural state, but what impacted me most was the hunters — not the animals.

“I was impressed by how they moved through the mountains, and how they tracked bears. I found all of this fascinating, so much that I thought I wanted to know more about their lifestyle.”

It took time and commitment for the Matagi communities to accept a woman on the mountains alongside the men. They believed Yama-no-Kami was a goddess of the mountain who was envious of other women in her sacred domain. This belief created a deep-seated barrier for women. But as they were faced with the fear of the Matagi legacy and way of life dying out, a door opened for Hiroko.

She explains, “For all of them, the absence of successors is a very present issue. They think the number of Matagi would be greatly reduced if women were still being rejected.”

The acceptance process for Hiroko was long. It required three years of training and tests before she was fully integrated into the group. This was a time to not only test Hiroko’s resolve, but the acceptance of her presence in the mountains by Yama-no-Kami.

“When they accepted me, I remember feeling a huge responsibility for what that meant,” she says.

Hiroko has lived in the Matagi community of Oguni for over nine years and recently had a daughter — a fragile hope that hers will not be the last generation of Matagi.

shrines in the woods to pray for their protection and

beg for fortune to the mountain goddess, Yama-noKami. The red gates represent the frontier between

the earthly world of humans and the mountain realm

of the deity. Once they cross it, they are obliged to

follow a strict code of conduct. The Matagi consider

everyday language too impure for use in sacred

territory. They developed “yama-no-kotoba,”

a language they could use exclusively in the

mountains. In Japanese, “bear” is “kuma,” but in the

mountains, Matagi say, “itazu.” Before the hunting

season, every Matagi hunter trains to master this

unique language — a wrong word can lead to

expulsion from the expedition.

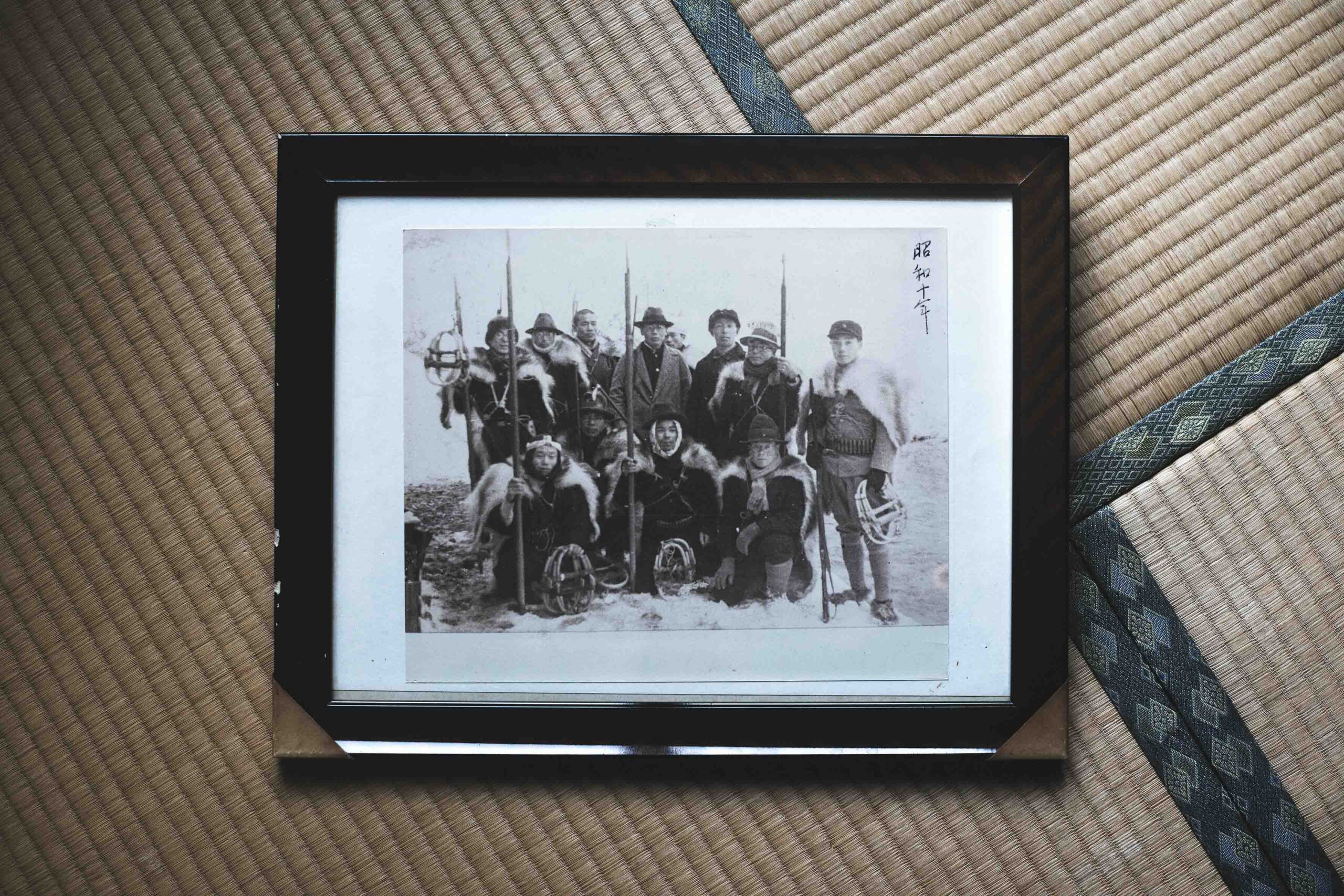

Matagi hunters from Oguni. For hundreds of years,

Matagi have been practicing the “encompassing

hunt” — a method which involved up to thirty

individuals surrounding an entire watershed to

push bears to an ambush point. With the shift in

technology from spears to rifles after World War II

and the dwindling population of Matagi, this method is rarely practiced today

line in Animatagi. His grandfather Tatsugoro, was

considered a legend among the matagi hunters. It

is said that in one occasion he shot down a bear

without even touching it, which earned him the

nickname “Tatsu, the air thrower”. In 1974, he

even traveled to the Himalayas with some matagi

colleagues, with the intention of hunting the Yeti.

of Animatagi, examines a Matagi relic that has

been in his family for several generations. The

knife originates from the 19th century and is

characterized by a hollow hilt through which a

wooden stick could be attached and used as a

spear. Hideo Suzuki comes from a long and notable

family line in Animatagi. His grandfather, Tatsugoro,

was considered a legend among the Matagi

hunters. It is said he struck down a bear without

even touching it, which earned him the nickname

“Tatsu, the air thrower.”

separating the paws of the animal from the rest of

the body before proceeding to skin the bear. Belief

dictates that parts of the bear (viscera) must remain

on the mountain as an offering to the Yama-no-Kami

— the mountain goddess personifying the conscious

presence of nature. She grants them permission

to hunt in her domains, but in exchange expects

responsible and respectful behavior toward the

natural world. If hunters abuse their privilege and

take more than they need, any favors afforded them

will be retracted.

skinned. The Matagi believe in marking the

boundaries between mountains and villages to

prevent wild animal confrontations. Every year,

Matagi leaders meet with local city council officials

to discuss the wildlife situation in their region.

Together, they establish the limits of the hunting

season. The Matagi are known for their intimate

knowledge of the mountains and the local flora and fauna.

the day’s hunting excursion to his companions. He

belongs to an independent group of Matagi hunters

in the village of Oguni. Establishing clear boundaries

for each hunting area is a critical task. Shigemi is

a mentor within the community and was the first to suggest accepting women into the Matagi way of life.

a 94-year-old former hunter. Currently they run an

‘onsen’, a traditional Japanese inn with hot springs, in

the village of Oguni. Due to the fact that in modern

times hunting alone is not economically sustainable,

many former hunters have had to look for labor

alternatives in very diverse sectors.

is one of the best scouts in the group — her role

is to locate bears on the slopes of the mountain.

Allowing women to become Matagi hunters may be

the critical lifeblood keeping these traditions alive for future generations.

Read the full article here